The tragic death of Graham Thorpe and what we must learn about men and depression

The former England cricketer was a model of handling oneself with strength and style. His death by suicide came as a shock to many, but not to Horatio Clare. Having struggled with his own monsters of the mind, he explains why men are more at risk than any other group

Watching Graham Thorpe at the height of his powers, in the 100 Test matches in which he represented England as a formidable batter, was a wonderful experience. In the first test against Australia in 1997, for example, he chopped, cut and drove his way through a mighty attack.

Shane Warne and Glenn McGrath were the best bowlers in the world, but Thorpe defeated them with such elegance and skill that the commentator Richie Benaud remarked, when Thorpe’s first 50 runs came up: “There has hardly been a moment when Graham Thorpe has looked anything but at ease.”

From such ease under pressure to this week’s awful news of Thorpe’s death by suicide is a tragic journey, one of over 4,000 carried out by desperate men and boys in Britain every year, and a moment to think very seriously about this scourge of our mental health.

Thorpe’s professional life was a model of handling oneself with absolute strength and elan. He was a man in full, a loving and beloved husband, father and friend, and that he took his own life is heartbreaking, and touches a personal pain.

I have been working in the field of mental health for years, interviewing, researching and writing about what we know about the mind’s troubles and crises, and what progress we are making in understanding and treating the worst of them. This work is very close to me: my dear sister took her own life in 2011, and I had a breakdown in 2018, which saw me sectioned for a couple of weeks in a psychiatric hospital.

My heart goes out to Thorpe’s family now. The question you are left with burns right through you: what could anyone have done to prevent it?

Like all mental illnesses, depression is a spectrum. It can be a normal reaction (though it does not feel like that at all) to an unhappy life situation. If you are miserable in your job or your relationship, if you are worried about money and your future, if you are socially isolated and feeling terribly alone, then depression is a reasonable response; a message to yourself to make changes.

If you cannot make them and do not seek help, it can and does worsen. I believe it was depression like this that pushed my brilliant and beautiful sister Janey down a slope to a misery she could not endure, which became lethal.

Because they admirably and valiantly wish to raise awareness and help fight suicide, Thorpe’s family have said publicly that he had been “suffering from depression and anxiety” for some years.

For anyone who knows those monsters, from the inside or in a loved one, that statement summons a world of suffering. Suffering is not relative. Even a short and explicable brush with depression feels like raw hell. To fight it for years is an exhausting nightmare. You need the best care, and you need to be lucky – and not even the wealthy and the well-informed are guaranteed those.

The former England cricketer had been treated in hospital in 2022. The details are private, but it would be normal to give someone in this position medication. Antipsychotics can help even dire and deluded states. (Clinicians drained my madness out of me with two doses of quetiapine.)

They can act as mood stabilisers for years. Psychiatrists and GPs also commonly prescribe antidepressants, which can affect neurotransmitters in the brain, leading to an improvement in mood and feelings.

Medication has salved and saved hundreds of thousands of people. However, psychiatric medication is fallible. Pills can take weeks to work, which can be dangerous. And, for many, they do not work at all: up to 30 per cent of patients will experience no significant change. Individuals with similar conditions react differently to drugs, so psychiatrists prescribe by trial, error, and side effects.

Effectively, you and your clinician experiment on your brain and body, searching for a drug that suits you. But drugs don’t necessarily work for ever. Sufferers can find themselves taking multiple medications, and struggling with webs of side effects – some of which can include suicidality.

If two different classes of antidepressant fail to help, you are diagnosed with “treatment-resistant depression”, but there are still treatments. Therapy can be a lifesaver, especially trauma therapies like eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing.

In other countries, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is commonly offered. Britain is reluctant to deploy it compared with France, for example, though ECT has a good success rate. Many psychiatrists say they would opt for ECT. However, one sufferer I interviewed stopped having it because she could not do her job with the memory loss that ECT can cause.

The problem is the complexity of the human brain. The “default mode network” plays a key role in depression. When you stop concentrating on anything specific, those background thoughts are coming from this network. During our worst lows, we experience them as an endless repetitive drumbeat of despair. Mine go, “You are awful, you wreck everything, your family will be better off without you, you should end it.”

Neuroscientists believe that the default mode network, in which impulses pass between different structures in the brain, is a physical, electrical and chemical architecture, acting as a circuit for these thoughts.

This may explain how the blast of electricity from ECT disrupts them. It also explains the remarkable success of trials of ketamine and psilocybin. These substances, administered clinically, have strong positive effects on the network circuitry of impulses, freeing thoughts and feelings.

During our worst lows, we experience them as an endless repetitive drumbeat of despair. Mine go, ‘You are awful, you wreck everything, your family will be better off without you, you should end it’

Ketamine and psilocybin also can act as distributors for the brain-derived neurotrophic factor proteins, which act as a fertiliser on dendrites – growing parts of brain cells themselves. They both work almost immediately, offering huge hope for future sufferers of depression.

These advances will save lives, hopefully very many lives, but they are unlikely to change the awful equation of suicide. While women are more likely to attempt it, men are more likely to die by it. Three-quarters of suicides are carried out by men; it is the biggest killer of men under 50. Men who are not well off and living in deprived areas are the most vulnerable.

Research shows that men overall are less likely to talk about their troubles, less likely to seek help, and therefore less likely to receive a diagnosis and treatment. There is much we can do to publicise the importance and effectiveness of speaking up and asking for care, but we need a deep shift in the culture of men and our thinking.

An alarming report by the Samaritans in 2020 found that the men who are most at risk are also the most unlikely to make use of doctors, support groups or community resources. Some stubborn part of the male instinctive brain seems to feel we should fight on alone, and crucifies us when we cannot win alone.

Superb institutions such as the suicide prevention group Andy’s Man Club report that men find their lives and hopes are saved by sharing with each other. The first visit, which is so very hard, makes a huge difference – but when I was last down, I could not find the courage for it. I thought I wasn’t suicidal enough – a very male idea. I am beyond fortunate that I have had years of time, information and work to make sense of my mental health and look after it.

Since the pandemic, huge numbers of us have become more conscious and careful of our own and each other’s mental health, and we are teaching each other and our children that this is a normal and adjustable part of life. But the difference between mental health and mental illness is important, too.

Most of us will avoid severe mental illnesses like the clinical depression that killed Thorpe and my dear sister. All they ask of us is that we take care of each other, love their memories, and fight in their name for more information, funding, research, and ambitious policies to save others from their fate.

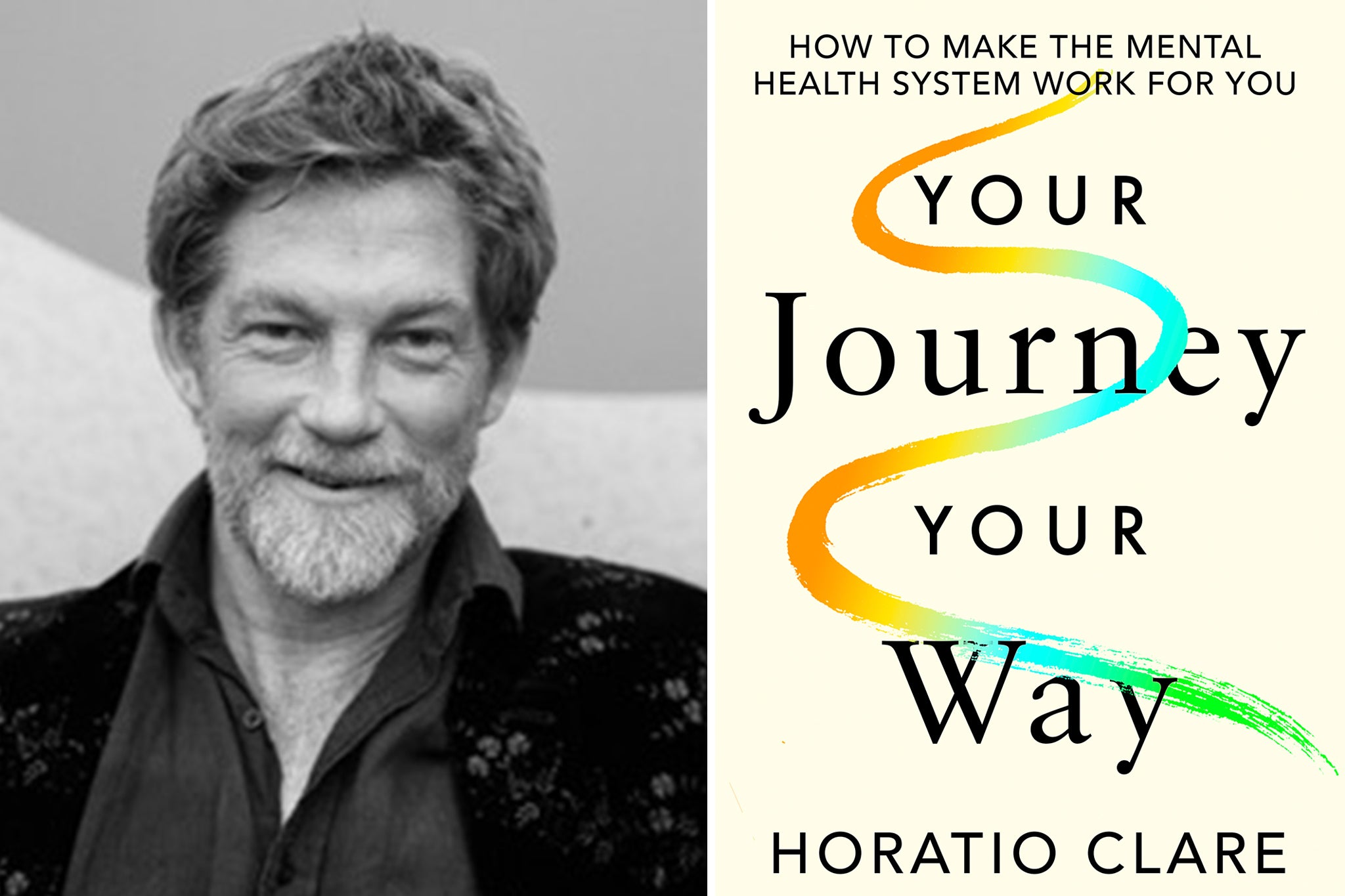

Horatio Clare’s new book, ‘Your Journey Your Way: How to Make the Mental Health System Work for You’, is published by Penguin Life on 29 August and is available for pre-order now.

If you are experiencing feelings of distress, or are struggling to cope, you can speak to the Samaritans, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch.

If you are based in the USA, and you or someone you know needs mental health assistance right now, call or text 988, or visit 988lifeline.org to access online chat from the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. This is a free, confidential crisis hotline that is available to everyone 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

If you are in another country, you can go to www.befrienders.org to find a helpline near you

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments